Why I memorize openings

10 minutes a day can set you up for more valuable learning experiences.My opponent's rating was 300 points higher than mine, so I wasn't expecting a win. And I did, in fact, lose. But I was hoping for an enjoyable game and a good learning experience, so the disappointing thing was that I got neither of those.

This was about two years ago. I was new to the opening (the Open Tarrasch variation of the French Defense) and was out of book when we got to this position.

Developing my light-squared bishop seemed like the logical next step, and two squares seemed like reasonable destinations: e2 and b5. I mentally flipped a coin and played Be2.

That was the wrong move. I got a cramped position and an unpleasant middlegame, and went on to lose.

In reviewing the game, after learning Bb5 was the better move, I could’ve also tried to learn something from the experience of playing the middlegame with the bishop on e2. But what would be the point? I’m not going to put the bishop there in the future. And so the experience - the extremely valuable, for chess improvement purposes, experience, of a tournament game - was squandered.

Yes, the game gave me a strong appreciation for why Be2 was an inferior move. But so what? I would’ve been better off learning Bb5 in 10 seconds, and spending that two hours doing something else.

Let’s do a cost-benefit analysis

The benefits of memorizing openings are not great. It’s rare that opening knowledge is the thing that determines the result of a game, at the amateur level.

But the costs are not great either.

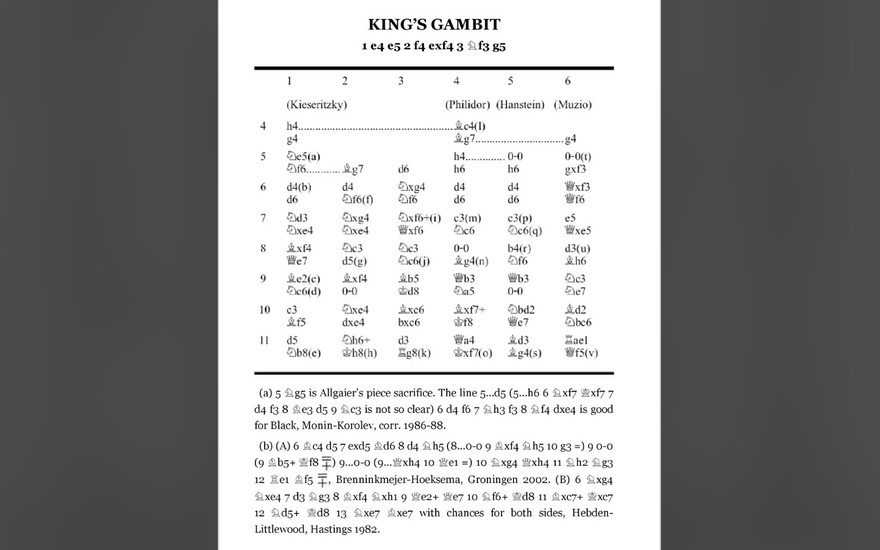

I spend about 10 minutes a day drilling openings using the King’s Cross app for iOS, and as a result I have 2,540 opening moves memorized, in a couple dozen openings. And I memorize a lot more than I need to (because I enjoy it). I think you could get by with a lot less - 10 minutes a week, perhaps - if you select your openings to economize on theory.

(King’s Cross is great if you want to create your own lines, which I do because I find it interesting. It doesn’t manage a study schedule; I have to do that separately. If that process doesn’t appeal to you, other apps like Chessable and Chessbook are also good.)

Two tangible benefits of memorizing openings

Personally I hate the feeling of being in an unfamiliar position where I don’t know what to do, when the game has just started. But that’s intangible. Here are two tangible reasons memorizing more moves helps:

- You save time on the clock. I’ve had on-and-off problems with time trouble, and memorizing more openings has helped with that.

- You get more valuable learning experiences. Having your pieces in the right places makes it more likely that the lesson you take away from the game is something you could’ve only gotten from the experience of playing a game.

There are wrong ways to memorize openings

Memorizing moves you don’t understand is wrong. Cutting off your memorized line in the middle of a critical variation is wrong. Memorizing moves you’re unlikely to face is wrong, and to that end the database of games played by amateurs on Lichess is essential for knowing what moves opponents at your level play most often. Good Chessable courses use this resource. Bad ones - or ones that are written for an audience of masters only - don’t.

Memorizing your favorite openings while neglecting others is another common mistake. Are you ready if someone plays the Trompowsky against you? What about the Nimzo-Larsen Attack? You should be. It’s not hard.

Chess should be fun

Playing that game with my bishop on e2 wasn’t just a squandered opportunity. It was also unpleasant. Chess is optional; I don’t want to do it if it’s unpleasant! I want an interesting game where my pieces start off in the right places. This is possible when I learn these lessons about opening moves not from games that last two hours, but from opening drills that last five minutes.

More blog posts by danbock

11 things I did to take my USCF rating from 1547 to 1976

I’ve had some ups and down in the year since my first blog post, where I wrote about what was workin…

What really decides games at the USCF 1900 level

It's dumber than you think.

My two favorite chess tournaments

US Amateur Team East and ALTO are the best in-person chess experiences I've found.